If Carlsberg made rivers, they would make the Whanganui. It really is everything a river should be: Wet, winding, steep-banked, gorge-framed, tree-lined, tumbling and with a flow that can change from gentle stream to raging torrent on the flip of a dime. But I know, you know (that we know) rivers are about so much more than physicality. A World class river needs to offer the full package. It needs personality too. And let it be known – the Whanganui’s got swagger.

If I were following the Te Araroa trail to the letter, I should have kayaked the Whanganui. Indeed the stretch from Mangapurua Landing to Whanganui itself is one of New Zealand’s 9 ‘great walks’ (no that doesn’t make sense to me either). It’s a good job that I’m not a stickler for the rules then, and instead of a 5 day kayak I opted to run the 90km along the river road. A road so steeped in history that it made me gasp and giggle with glee. Here’s a few firm favourites:

JERUSALEM AND THE POET

Probably the most famous of settlements along the Whanganui is the small town of Jerusalem. Previously a fishing village, it became the site of a Roman catholic mission in 1854. It was here that Sister Suzanne Aubert later founded ‘The Order of Compassion’, which offered sanctuary to abandoned Pākehā (fair skinned/ non-Māori) children from Wellington.

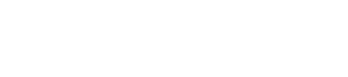

In the century that followed, Jerusalem attracted it’s fair share of celebs. Most notably the poet James K. Baxter, who established a commune at the town in 1969. With the aim of understanding life from ‘the Māori side of the fence’ Baxter pioneered a community based on values of voluntary poverty, Catholicism and Māori spirituality. He described his ‘rules’ for community living in the 1971 Jerusalem Daybook:

Feed the hungry;

Give drink to the thirsty;

Give clothes to those who lack them;

Give hospitality to strangers;

Look after the sick;

Bail people out of jail, visit them in jail, and look after them when they come out of jail;

Go to neighbours’ funerals;

Tell other ignorant people what you in your ignorance think you know;

Help the doubtful to clarify their minds and make their own decisions;

Console the sad;

Reprove sinners, but gently, brother, gently;

Forgive what seems to be harm done to yourself;

Put up with difficult people;

Pray for whatever has life, including the spirits of the dead.

Upon speaking to those who live along the river today I discovered some more exotic tales about Baxter’s commune. Legend has it that each year, dozens of women would make the pilgrimage up the river road, just to ‘be’ with the poet. The Postman on duty during Baxter’s residency reported getting quite a shock when delivering mail – as several bare breasted beauties would emerge from the grounds to greet him. Then there’s the story about a driver who was unable to continue on up the road, because Baxter was in the middle of it, making sweet Whanganui love to one of his lady friends. I can only assume that the poet was trying to teach the driver to ‘put up with the difficult people‘ or ‘give clothes to those who lack them’ .

Jerusalem’s glory days have long since passed, and it’s now a hidden gem – home to a modest Māori community and frequented by small groups of tourists. It’s an undoubtedly special place, and I could see why an artistic soul like Baxter’s would have felt so at home here. On an autumn day, the sight of the evening sun wrapped around the spire of the hilltop church is breathtaking. The grounds are still beautifully maintained by two sisters of ‘The Order’, and the sizeable St Joseph’s convent remains immaculate – offering a bed to those who might be in need as they pass through.

OHU AND THE HIPPIES

Back in the 1970’s, with flower power drawing to a close, the New Zealand government launched a scheme that allowed land to be leased to groups who wanted to set up co-operative communities, called Ohu. Of these co-operatives, the one that lasted the longest was the Ahu Ahu Ohu, on the Whanganui river.

Access to Ahu Ahu was deliberately complex. It could only be reached by canoeing across the river to a track entrance, then hiking for 90 minutes deep into the bush. Over the years, six couples made Ahu Ahu their home. They built a dairy, cold stores, bee keeping facilities, generated their own power, and used the location’s unique and sheltered microclimate to grow vegetables and nurture orchards. As time passed, the couples had families of their own. One child born at the Ohu was named… (wait for it) Misty Moon Beam.

Sadly Misty no longer lives at Ahu Ahu, and has instead made Whanganui town her home. The community survived until 2000, when after several efforts to keep its history alive, the land was reclaimed by the government. Today many of the buildings have been removed for safety reasons, but if you know where to look, you can still take a boat across the river from Te Tuhi landing and a hike up the old track to the secluded spot.

TONGARIRO

I was sad to leave the shores of the Whanganui river, but I’d literally run to the end of the line, by land at least. From the old tourist town of Pipiriki, I turned Eastwards and made for Ohakune – a laid back town with a traditional alpine vibe. From there I spent a day running uphill on what I later learnt to be the longest paved road ascent in New Zealand. At long last I entered into Tongariro National Park.

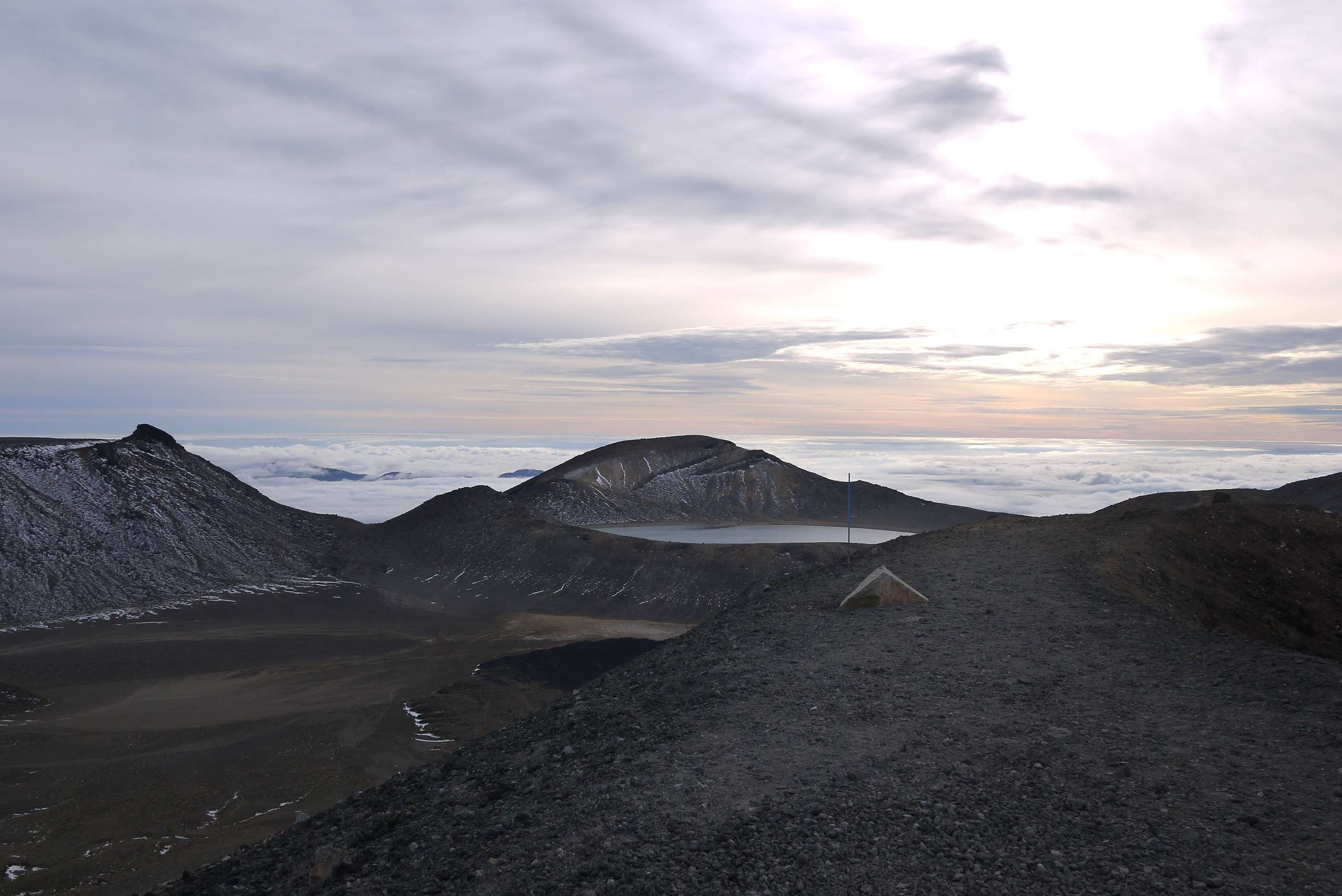

Tongariro National Park is, and I apologise for the lack of variety in vocabulary, frickin’ awesome. It arrives on the horizon, completely unannounced. There I am scampering along in lush, gently rolling green hills, and Boom! Ruddy great snow capped mountains in the middle of a volcanic martian landscape, all up in my face. From some 100km away you can see the peaks of Tongariro, Ruapehu and Ngaruhoe – all of which differ in size and style (yes mountains have style).

Once I’d clapped eyes on the most visible – Ruapehu – I couldn’t stop staring. It is majestic. If mountains were Lord of The Rings characters Ruapehu would be Gandalf. Something about its presence on the horizon makes you feel like everything is going to be okay. It puts the beauty of the planet and life itself into perspective.

CROSSING DAY

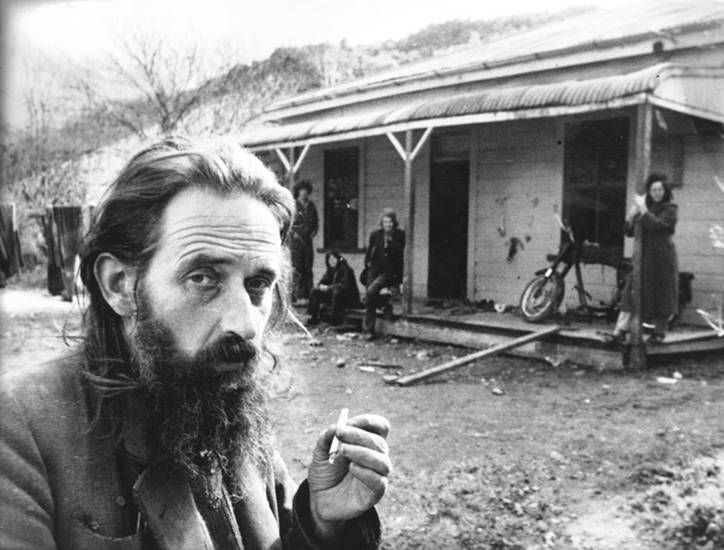

I’ll admit that I was nervous about the Tongariro Crossing. It was to be the last high point of the trip. The final place where I needed to seriously consider the weather, and be prepared to wait out anything less than a clear and fine day. Each year dozens of tourists are rescued from the crossing. Just last week a young German lad slipped and narrowly avoided a fatal fall. Granted, many rescues are due to the fact that the individual is a particularly special breed of muppet, and has decided to take on what is a serious alpine pass in a t-shirt, board shorts and flip flops. But others are well prepared hikers, who find themselves genuinely caught out. There’s no denying that Tongariro deserves a due amount of respect. That said, in comparison to the precarious places I’ve found myself scrambling, sliding and crawling along in the South island – Tongariro was a pussycat. And because I found it to be mostly pussycat like, I had a whale of a time trotting along its wide and beautifully graded pathway. There were even steps should the trail get too steep. Steps I tell you.

I opted for an early start and was on the trail just before dawn. After padding past a few keen tourists, I reached the top plateau at 8.30am. To my surprise, I was entirely alone. Clouds danced in the valley to the North, and the sky glowed in a mix of peach and scarlet hues – a remnant of what had been a near perfect sunrise. It was a humbling place. I stayed up there for for 15 minutes, enjoying the solitude and reflecting on the times over the past few months that I’d thought about making it to this point. I realised that this had to be one of the greatest gifts an adventure, or indeed any form of travel has to offer. To transform what were once letters on a map, contour lines, areas of shaded grey into a place that grabs you so tightly by the emotional nutsack that you can barely breathe. Once merely a name that I’d scribbled in my notepad, Tongariro had now become a full blown memory, and one that I’d cherish at that.

ONWARDS

And that’s it for today kiddywinks! I’m being chased by old man Winter as I make my way North and into the final 800km of the trip. In some ways thats not far to go at all, and yet I have a feeling some of the hardest yards could lie ahead.

Until next time,

Big Love,

McNuff xx

If reading this post has put the ding in your dong and brightened up your week, you can help me brighten up the lives of some kids by sending them on adventures. Spondoolies gratefully received for the little guys here

Hi Anna

I met you in a cafe in Paekakariki when you were running through the Kapiti Coast. Good to see the tales of your trip up the beautiful Whanganui River including the information about the Ahu Ahu Ohu. I lived at Ahu Ahu for six months in the early 1970s and interesting to see the photo of the community building all these years later. Good luck with the rest of your run.

Hi Paul, that’s so exciting that you lived there! You’ll have to excuse any inaccuracies then – there are so many different tales and sources. I’d have loved to have heard about it from you. If only I’d known when we met!! I honestly loved the river road, among my favourite sections of the whole trip. I stayed with the couple at Omaka farm, who were lovely. Great to meet you, all the best! Anna

hello Anna,

We follow yur trip with admiration!!! since you leaved us in Drummond, with Applebye family…

Now, we come back home, after au short 3 mounths touristic tour… (piedsenhaut.blogspot.fr).. if you remember the french people who shared a nice evening with this servas family.

BRAVO!

Marie Thérèse (and Yves)

Hello you two! Of course I remember you, how could I forget! I must apologise, I wrote a reply to your last lovely email when you were near the Red rock, but it failed to send. Thank you for writing again – I can’t believe you’re back home! I hope you had a wonderful adventure.

Not long to go now, it should take me 4 weeks or so to make Cape Reigna… Wahooo 🙂

I hope you’re getting a nice start to spring back home,

Anna

Go go Anna! Thanks for another lovely write up – it is great sharing your challenges and fun. Best wishes from the Colleys of River End